Index

Microorganisms are all around us, but what are they? A quiz to find out how they work

Observing microorganisms grown on a petri dish “Why are there some places where they don’t grow?”

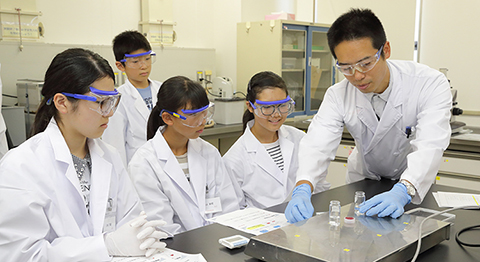

The Tohoku University Science Campus is showing children the fun of science. For the first half of this article, we presented an interview about how this event came to be. For the second half, we describe the “Bio Adventure: Microorganisms are Hard Workers” lesson held on October 5, 2019.

Microorganisms are all around us, but what are they?

A quiz to find out how they work

The “Bio Adventure: Microorganisms are Hard Workers” program, provided by Kyowa Kirin, was presented on Saturday, October 5, 2019. The 24 children taking part were in the third to fifth year of elementary school, and were among more than 80 applicants for the program.

A researcher from Kyowa Kirin wearing a lab coat presented the program.

“First, an experiment!”

The children dissolved sugar in lukewarm water, added a “mysterious powder” and covered the container with a box, and left it during the lesson, to be looked at later.

The presenter asked,

“What is a microorganism? Do you know what microorganisms there are?”

“Euglena?” “Volvox?” “Yeast?”

Some knowledgeable children called out.

“You might think that microorganisms are a little bit scary. But not all of them are scary. We currently know of about 100,000 types of microorganisms, but only a very few of those do bad things. The other microorganisms either don’t do anything bad, or they do good things for us. Today, we’re going to talk about the good microorganisms.”

“Where do you think microorganisms are?” The presenter continued the lesson, repeatedly stopping to ask questions. Rather than being told the answer right away, in this lesson the children have to think for themselves.

“Work by microorganisms that helps us in our daily lives is called “fermentation.” There are things that are made by fermentation all around you. Now, a quiz question! When microorganisms eat raw materials, what do they change them into?”

Observing microorganisms grown on a petri dish

“Why are there some places where they don’t grow?”

“Have you started to see how interesting microorganisms are? How large do you think they are? They’re about 0.006 mm in size, 500 times smaller than that small sesame seed. So small you can’t see them. So how can you look at them? One way is to grow them until they become visible!”

For this program, the participants had been given an exercise to do in advance: applying something they wanted to observe to a petri dish with an agar culture medium.

The children had sampled microorganisms from an assortment of odd places, including “my mom’s iPad,” “a rhinoceros beetle” and “the nail and heel of my right foot.” When microorganisms grow into a group, this group is called a “colony.”

While the lively children were looking at each other’s petri dishes, each table also threw out questions for the researchers.

“Why are the colonies round?”

“That’s a good question! Why do you think that is?“

“Did you see a petri dish like this? There are two colonies, one of bacteria and the other of blue mold. No bacteria are growing around the blue mold colony.“

“Blue mold puts out a substance around itself that stops other microorganisms from growing. It’s called an ‘antibiotic’—have you heard of it? It’s the ingredient in drugs like penicillin or ivermectin. Thanks to antibiotics, we have a way to treat infections caused by microorganisms. Out of 24 petri dishes, we’ve found one with blue mold. A round of applause!“

Ivermectin, a type of pesticide, is also a drug for tropical disease prevalent mainly in Africa that has saved the lives of many people. It is made from a compound produced by a microorganism that was discovered by Professor Satoshi Omura of Kitasato University, who won the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the achievement. In fact, Professor Omura is a great golf enthusiast, and he discovered the new species of microorganism that led to the discovery of ivermectin from soil sampled near a golf course in Shizuoka.

“Isn’t it funny that a Nobel prize-winning discovery came from a piece of soil you might see every day? Now, what’s happened to the ‘mysterious powder’ from our first experiment? Don’t you want to find out?“

Through the microscopes, the children observe a world that is usually invisible, and take home special photographs of it

“Now for the second way to look at microorganisms that are too small to see. Let’s observe it under a microscope!“

The children made slides from three household materials like cheese and yogurt drink and observed them. Looking through the microscopes with attached monitors, they saw a world that is normally invisible to them.

Microorganisms were first discovered by a Dutchman, van Leeuwenhoek, who found them by looking through a microscope that he made himself. The observation proceeded combined with a discussion of the history of the development of science and technology. Finally, the children pressed the shutter button to take a special photograph all of their own.

“The cheese was the best,” “I like this part”—they each photographed their favorite area.

As time passed, the children became engrossed and the atmosphere in the hall became relaxed and informal. At the end of the session, too, as they looked back on what they have learned, they enthusiastically raised their hands and answered questions.

The researcher presenting the lesson commented as follows.

“I’m always surprised by the fresh observations children have. Today, I was glad to see that even the children who were looking at the floor at first became so involved by the end that they didn’t want to stop looking through the microscopes. The number of experiments in schools is increasing too, and I hope that today’s experience is an opportunity for them to get to like science.“